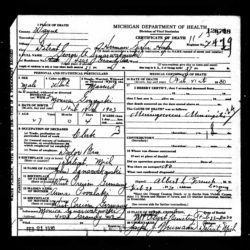

George and Robert Sznarwakowski were only 17 and 15 when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, but they were effectively adults courtesy of the hardships of the Great Depression and their father’s sudden death over 10 years earlier from “meningoccus meningitis” on February 21, 1930.

In reading old newspapers to flesh out the story told by census and directories, this tumultuous period in a city that was on a meteoric rise came painfully into focus – a blend of family tragedy in losing their father with national and world events.

Papa (Robert) has written of his older brother starting work after school when George was 12 – some time after September 1936 – in Parker’s Butcher Shop, at a time when work was still hard to come by. The worst of the depression brought 25% unemployment, although after 1933, things were slowly improving – it can’t have been easy for children with so many adults looking for whatever work they could find. Papa recalls selling newspapers, setting pins in a bowling alley and helping with weekend bicycle deliveries at the butcher shop where George worked. By this time they had lost the house on 4203 Grandy Street, which had been their grandparents John & Anna’s home since 1905.

Between the time when their father George was born in 1903 and Papa was born in 1926, Detroit grew from the 13th largest US city to the fourth, and its population exploded to more than five times the 285,000 it was in the 1900 census. If anyone is interested in Detroit’s view of itself from a short history and look forward from the 1920 Polk City Directory, I’ve put a section of the pages here. The time from automobile-driven boom to depression bust was just 30 years.

In 1920, when he was 17, Papa’s father George is listed as a clerk at the Detroit Free Press, Detroit’s largest newspaper. Monica Gorzynski, a first-generation immigrant who had arrived with her family in 1914, and George married in January 1924 and moved in with her parents. George’s older (adoptive) sister Gertrude and her husband were living with John Sznarwakowski on Grandy (Anna had died of stomach cancer in 1922).

By 1928, George is listed as an interpreter and they are living in the house on Grandy – Gertrude and her husband had their own house and John was living with them (in the 1930 census). The families were all getting by, but there was no cushion for emergencies

In 1930, Monica – as Mollie H Snover, widow of George A, was listed in the Polk City Directory at 3411 East Warren Avenue, but I don’t know where the family lived between 1932 and Parker Street in 1943. I haven’t found any of them in the 1940 census yet. I also don’t know why Monica went by Mollie and this is her earliest use of the last name Snover I’ve found so far.

Surprisingly, I found that Papa’s grandfather John had used the name Snover for two years in the city directory – 1915 and 1916 – before reverting to Sznarwakowski afterwards. It can’t have been that Sznarwakowski was easy to spell – I’m up to 21 different spellings in the various sources and I may not have found them all yet!

Papa remembers getting cheap “day old” bread at the Indian Village Bakery – at 8201 Mack Avenue – three blocks from their house, so they may have been somewhere on Parker Street, though not at 3629 Parker (the address George gave on his marriage license in 1943, which they were not occupying in the 1940 census). You can view the known locations on this custom Google map.

George was working at 12 and Papa not long after even though in 1933, as part of a massive set of regulations on wages and hours, combatting the depression, work for minors was banned except for part time work for14 and older up to 3 hours a day. I’m assuming enforcement was lax and it let employers go below the minimum wage – another new concept as part of the New Deal.

Minimum wage varied by what you did and where you lived (more in the cities than in small towns or rural areas). 30 cents an hour to mill flour or manufacture toys; 45 cents an hour servicing oil burners. Papa didn’t say what George made when he started working for the butcher full time around 1939, but when Papa quit school to work at Tom’s Quality Market, around 1941, he made 25 cents an hour. That sounds very low – even in 2018 terms, it’s only about $4.50 an hour – and it appears to be below the minimum wage for unskilled/semi-skilled workers of 30-35 cents an hour at the time. But the income from the two Sznarwakowski boys was key to keeping the family – their mother Monica, and younger sisters Mary and Phyllis – afloat.

Starting in 1940, a huge federal rearmament program was begun and ensuring adequate labor for work in defense industries was a priority. Workweeks were extended again – to 48 hours from 40 – and cutting back hours as the auto factories had done early in the depression (to 32 hours a week) was ancient history. The newspaper help wanted sections were growing. That shifted into even higher gear as defense industries became war work after December 1941. The depression era bureaucracy for managing employment turned to ensuring that essential war industries got priority in hiring, except for those being drafted (initially those over 21, but that was reduced to 18 in November 1942).

George turned 18 on 24 Sept 1942 and registered for the draft; by January 1943 he was married and at the end of April he was in the Army Air Corps. Papa turned 17 and went to work for Gar Wood Industries at a factory building PT boats and tanks in March 1943, quickly learning to be an inspector and earning what he remembers as “very very good money”! He recalls they were able to buy a home – possibly 3629 Parker Street, but I’m not sure.

When Papa turned 18 and registered for the draft (March 1944) it didn’t take long for him to be inducted – 14 July 1944. After the US started widening the draft as the war ramped up, it set up benefits for both single and married draftees with dependents. Papa was the family’s sole support, so his $50 private’s pay was docked $22 to contribute towards the government dependents’ allowance. It was $68 a month for one parent with one brother or sister and $11 more for each additional sibling – so $79 for Monica and his sisters, about $1,200 in today’s terms.

Quite a step up from 25 cents an hour!