Searching the 1939 register to find John Walden Poulson – the Wastrel – I located him in Brighton – a place we have no family connections (that I know of). “Elm Grove Home (temporary)” was noted by the street addresses on Vernon Terrace were I found the Wastrel’s name.

A little digging in old newspapers and web searches revealed that in 1930 The Brighton Poor Law Union handed over responsibility to the local council and only the elderly and infirm remained in the Elm Grove Home. In 1935, The Brighton Municipal Hospital took over the workhouse building and the Elm Grove Home residents were moved to vacant properties in the area. The era of workhouses and Poor Law Unions was ending.

So far, I have no idea how or when John Walden ended up in this old people’s home for the poor, but he had turned 69 that January and I’m assuming things hadn’t looked up much (or at all) since the embezzlement problems in Goole, Yorkshire.

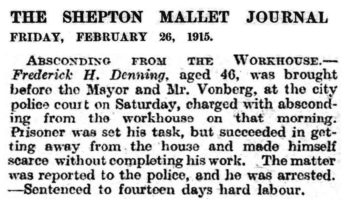

Since the early 1800s (The Vagrancy Act) sleeping on the streets or being without visible means of support was a criminal offense and could have you sent to the workhouse or prison, depending on the circumstances. It’s possible that the Wastrel was too old, tired (or drunk? That’s just based on family stories) to work or even defraud people. In some jurisdictions, it was a crime to abscond from the workhouse – you were there for a fixed time or until you could show you could support yourself. Some people were sentenced to hard labor for leaving – one example in this newspaper report from 1915 – seems truly mad from a 21st century perspective, and it certainly didn’t do anything to eradicate poverty or social problems.

The next record of John Walden Poulson is his death certificate – 18 May 1941 in St. Andrews Hospital, Bromley-by-Bow, Poplar, London. He died of myocarditis, an infection of the heart muscle – sometimes a complication of long-term alcohol consumption.The hospital was demolished in 2009.

The death certificate says John Walter Poulson, but as there were no family members around, this is likely just mishearing Walden as Walter. The occupation field says “of 41a Quaker Street Stepney, formerly a cashier” The informant is “F. G. Smith / Causing the body to be buried / 17 Ellerman Street Poplar”

Frederick G Smith is the hospital porter, 45 years old, and that’s his home address (found him in the 1939 register). So I have no idea where the body would have gone. St Andrews Hospital was, until 1921, the Poplar and Stepney Sick Assylum. In 1941 it was run by the London County Council and I assume they buried the body – it wasn’t left up to poor Frederick to improvise!

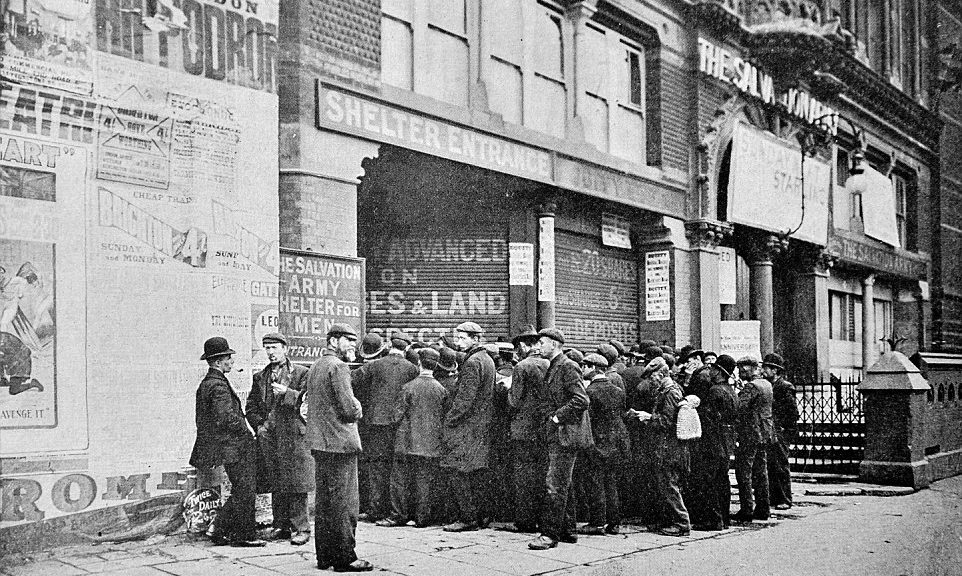

I did a little digging into the address on Quaker Street, and that was one of the early Salvation Army working man’s hotels – a dirt cheap lodging that was one step up from the shelters they were also opening all over the East End of London in the late 1800s. 41a Quaker Street was called “The Lighthouse” – they all had names. Perhaps it helped him keep the drinking in check.

I found an article about East London doss houses – not about this particular one – and have put a link online if you’d like some pictures from 1932 of something typical of where the Wastrel lived.

My father had a long list of favorite stories, one of which involved his Dad the bank manager (my grandfather; the Wastrel’s son) and a bank customer who sold off lumber on a wooded piece of land he owned that was security for a bank loan. I have no idea whether or not any of the story actually happened, but in the notebooks I collected after my father’s death – he’d been working on a memoir – were a short story version and play version of this tale of the bank manager and the gambler. In the story, the bank manager muses about the similarities between his difficult gambling customer and his own drunk and gambling father. The story says the bank manager’s wife insisted he go to see his father in hospital before he died:

“Five years ago my father died of an excess of drink, leaving a trail of gambling debts that make <bank customer>’s problems look like petty cash. He left home when I was six. I never saw him again until my wife made be go and see him in hospital just before he died. His contrition was too late, but it was a pitiful sight.”

This could all be dramatic license, and the age isn’t right as Gamps’ youngest sister – Ethel Suzanne – was born when Gamps was eight; he was 13 when the Wastrel got on the boat to Ontario Canada. How would the hospital have known to contact Gamps & Nanny? Possibly the Wastrel had stayed in touch with his oldest, Emily Muriel, who had been a witness at his third marriage? If they could get in touch with family, wouldn’t they have passed along the body rather than bear the expense of burying him?

I have searched old newspapers for more stories about John Walden getting in trouble with the law, and if he did, it wasn’t under his own name. It might not have suited Dad’s story, but I think the scale of the Wastrel’s swindles were probably not that large and except for home town newspapers – where his father’s good name made the Wastrel’s misdeeds a “story” – probably it wasn’t newsworthy.

A sad end to a sad story – with a trail of personal wreckage in the lives of family (one one has to assume friends too) along the way.