“l am satisfied that whether we make cheese at Dalgig among the mountains, at Cunning Park amongst forced grass, or among heather at Corwan, where Mr. Wason is making the desert to blossom as the rose, there is no difference whatever. My opinion is that good cheese can by good management be made anywhere, whether at the Land’s End or Caithness, if it be in the hands of a person who has something in the upper story.” Joseph Harding addressing the Ayrshire Agricultural Society in 1861. Having learned a lot about making great cheese and having tested his theories by teaching Scots farmers how to get equally great results, Joseph Harding’s views were now sought out.

It was no small incentive to his first fans, Scots farmers, that his cheese fetched £80 per cwt versus theirs only £50. Time for a field trip to see if they could improve. In 1854 an article in The Scotsman noted “In no department of farm management is the Scottish farmer so decidedly behind his English neighbour as in the manufacture of cheese.“

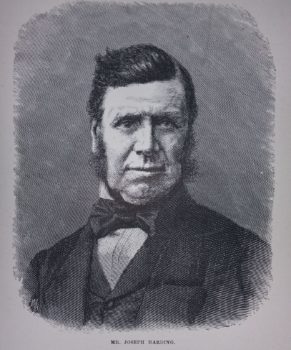

My stepmother Margo’s great-grandfather, Joseph Harding, came to be known as the father of Cheddar cheese. Fortunately, his letters to newspapers and stories about his work on improving the tools and methods for reliably producing great tasting cheese leave a paper trail we can follow back to Somerset in the 1800s. What is interesting is that his aunt, Elizabeth Harding, was a cheesemaker and was initially the senior member of a team that included her nephew Joseph and his daughter, Sophia (probably). Later, Joseph’s wife Rachel joined him making cheese and teaching.

To help anchor people, here’s a “pedigree” version of the family tree starting with my stepmother Margo

Margo was born in Taunton, Somerset in 1934, long after the industry-boosting improvements in cheese making of her maternal great grandfather, but as recently as 1937, a local (ish) newspaper, the Wiltshire Times, mentioned Joseph Harding’s role in a somewhat amped up tale of “…canny Scots…despatched a deputation to the West Country to discover what was possible about these superior local varieties of farmhouse cheese.” with the headline “What is Cheddar Cheese?” and a theme of stolen secrets, which isn’t really how things happened.

Joseph was a farmer who became known locally for the very high quality of his Cheddar cheese. From an 1866 article in the Western Gazette about the Exhibition of Dairy Produce in Paris: “...and when we state that two of the cheese to be exhibited are from the celebrated dairy of Mr. Joseph Harding, of Marksbury, who introduced the “Cheddar” system into Scotland, and who is considered to be about the best of Cheddar cheese makers, some idea may be obtained of the splendid quality of the cheese to be exhibited to our neighbours across the Channel.”

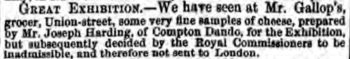

Joseph Harding first surfaces in newspaper articles in the 1850s. From the Bristol Mercury in December 1850, he is listed as a contributor to local goods sent for the 1851 Great Exhibition in Hyde Park: “Mr. Joseph Harding, Compton Dando: Sample of Somersetshire (Cheddar) cheese.” Sadly, a later report from May 1851 indicates that the Royal commissioners decided cheese wasn’t admissible, but you could buy it locally.

Local papers noted two of his children’s weddings in 1853 – both Emma and Mary Yeoman Harding married in the same church 19 January 1853. In October 1856, Joseph appealed his “poor’s rate” which was reduced. More interesting, a few lines down, it noted “Caroline and Ann Payne were charged with committing trifling felonies whilst in the service of Mr. Joseph Harding, Marksbury, but were both acquitted; they were defended by Mr. Steele, Bath, solicitor.” What on earth is a “trifling” felony? Misdemeanors are trifling, not felonies. And does this mean Harding accused two of his domestic staff in error? Sadly, I could find no other descriptions of this case.

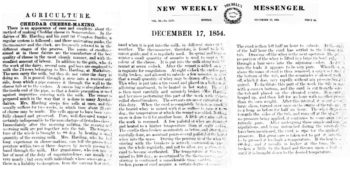

In 1854, the first articles talking about the Harding dairies – Mrs. Harding, nephew Joseph Harding and his daughter – and the visits to them of the Scots seeking to improve their cheeses appear. Prior to Harding’s work, the thought was that it was the pasture and climate that made the difference in the quality of the cheese. Harding showed clearly that was false. His approach mandated “…a regular system is followed; and those undeviating guides, the thermometer and the clock, are frequently referred to in the different stages of the process.”

From The Scotsman, in November 1854, an article talks about “The Ayrshire Agricultural Association, by deputing two of the members . . . to visit the cheese-making districts of the south. . . . In one extensive dairy of seventy-three cows, belonging to Mrs. Harding, they found the whole management superior.” They went on to note the higher prices she charged than they were able to. “ . . .if our Scottish cheese could be manufactured of equal quality with Mrs. Harding’s, the balance at many a farmer’s bank account would speedily assume more importance.”

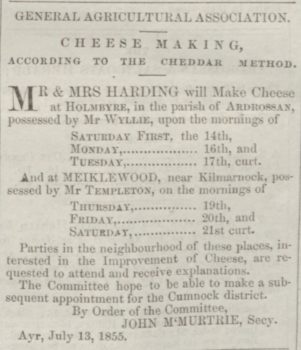

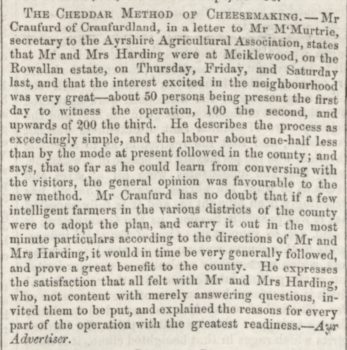

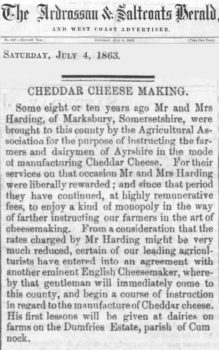

In July 1855, a short article in the Ardrossan Herald notes “The Ayrshire Agricultural Association are practically showing they desire to advance the manufacture of cheese in the county. They have brought Mr and Mrs Harding from Somersetshire, for the purpose of giving instructions in the Cheddar method of cheese making – a method, which according to the report published sometime ago by the deputation who had been sent to England to examine into the method, was considered much superior to the Ayrshire. They are likely to visit this district soon.”

By August, there’s an article that attendance is growing and the response to what was taught was very positive. In July 1859 a column called “The Farm” ran a piece on cheese-making which ran in many newspapers throughout the country. A report by Mr. Fulton of Temple Maryhill near Glasgow said that “it is clearly ascertained that the quality of the cheese is determined almost entirely by the mode of manufacture. … ‘Whilst in Ayrshire,’ writes Mr. Harding, ‘we made cheese in almost every part of the country . . . and the cheese was uniform in texture, quality and Flavour; if there was any sensible difference, our impression was that the best article was made at Corwar.‘” He followed that with a detailed tutorial.

In October 1859, Harding brought cheese he had made locally with his method to the Pembrokeshire Agricultural Society gathering, demonstrating that even in an area renowned for poor quality cheese, excellent cheese could be produced with the right process. Those attending the dinner after the show were able to taste the cheese and the verdict was “... there was but one opinion as to its richness and excellence. For Mr Harding to have succeeded in making a cheese of the Cheddar quality, in Pembrokeshire, where cheese-making has always been regarded as a stumbling-block, is indeed a triumph, equalled only by his generous offer to give any of his brother-farmers the benefit of his experience and knowledge in the art. ”

In January of 1863, Joseph Harding wrote a letter to the Ayrshire Express apparently somewhat tongue-in-cheek, playing up the idea that the Scots who visited him in 1854 had hoodwinked him into giving up his secrets. Here’s a part describing their departure: “With a kind invitation to pay them a visit to Scotland, they again left us for Bath, no doubt well pleased with their success in getting so cannily round the Englishman. Little more was thought of our Scotch visitors, until one morning I was surprised at receiving a packet by post, which proved to be a manuscript containing in detail, and very nearly correct, a description of the method of our cheese-making, with a polite request that I would point out any errors. I was greatly astonished, but it was too late to act on the defensive.”

That set off a cascade of unhappy responses – he’d been paid for his work with them and by then Harding’s name was well known, so the Ayr folk felt their reputations had been slighted. Harding tried to set things straight in a subsequent letter, saying that although what he said was true, he and the people who visited him always joked about this when they met. He described his original letter as “Indulging in a somewhat playful mood…” and said he wanted to continue a discussion about cheese making issues and this was supposed to be a light hearted introduction. Whether he made good on the hurt feelings is hard to say, but he did continue with a stream of letters on the subject of cheese making through the Winter and Spring of 1863. In July, a cheaper teacher was found to conduct classes in the area – it’s hard not to see a connection between these two events.

Harding was not the only teacher, but did continue to visit Ayrshire. A Mr. Norton who also taught at several Scots dairies in late Summer and Autumn 1863 (he was from Shepton Mallet and followed the Harding method with only minor variations) thought the local farmers were too inflexible in applying rules: “This leads them to make indifferent cheese by rule and good cheese by accident.” (Perthshire Advertiser, 3 Sep 1863)

I’ve placed some PDF files of the series of letters in 1863 and a few other detailed articles on Harding’s method in a Google Drive folder – a little light reading. There were other issues he opined upon in print – factory cheesemaking and Canadian cheddar – also included

Elizabeth Harding, Joseph’s aunt, died in 1865 – I was unable to find an obituary for her, but when Joseph Harding died in 1876, his Scottish pupils wrote an appreciative one. Farming continued in his family, including Eli George Jenkins (Julia Harding’s husband, a “Dairyman & Rennet Agent”) as well as George Gibbons, of Tunley Farm (Ellen’s husband, and Joseph’s executor). His name is still known enough that he has a Wikipedia page and a Google search gets you basic details on what he did – so definitely not forgotten.

Elizabeth Harding, Joseph’s aunt, died in 1865 – I was unable to find an obituary for her, but when Joseph Harding died in 1876, his Scottish pupils wrote an appreciative one. Farming continued in his family, including Eli George Jenkins (Julia Harding’s husband, a “Dairyman & Rennet Agent”) as well as George Gibbons, of Tunley Farm (Ellen’s husband, and Joseph’s executor). His name is still known enough that he has a Wikipedia page and a Google search gets you basic details on what he did – so definitely not forgotten.