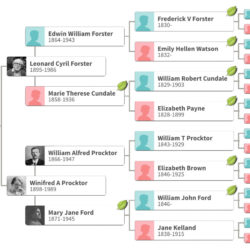

My mother’s stories about her Procktor ancestors, based presumably only on what her mother had told her, told a story of her great grandfather, a cabinetmaker, being a Quaker pioneer who went to Canada, returning to London when her grandfather was 12. It turns out the real story has no connection with Quakers at all (that I can find anyway).

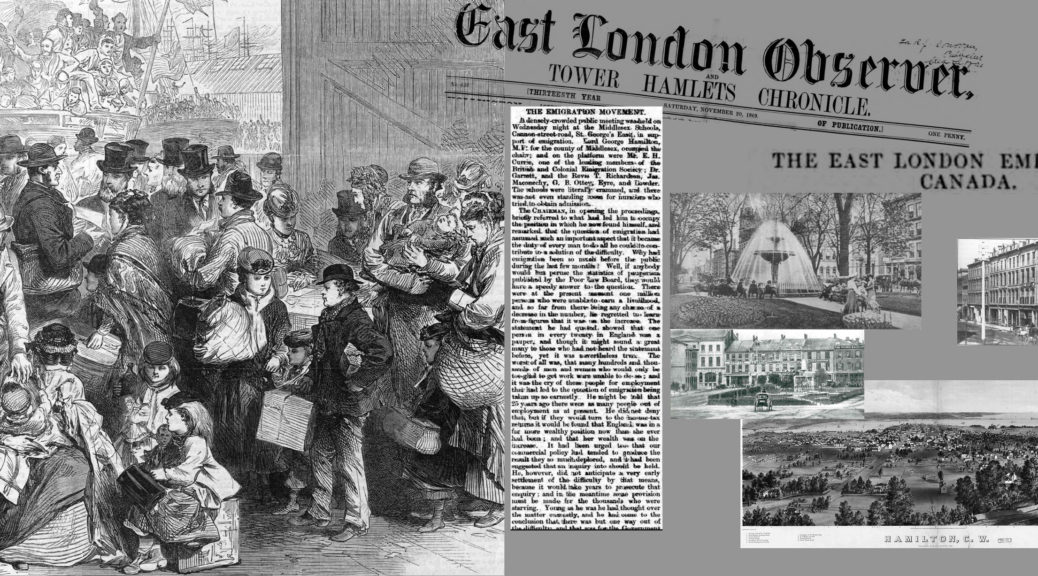

The move from the East End of London to Canada apparently stemmed from a need to find work in a time of high unemployment. I had no prior knowledge of the crash of 1866, but apparently the collapse of a London bank triggered a panic that affected unemployment rates for several years afterwards. In the East End of London, various charities worked on schemes to fund passage of the “deserving” unemployed to Canada – a dominion where more labor was needed. Out-of-work skilled tradespeople or agricultural laborers had no money to pay for their passage to Canada, and the government at the time took the view that it wasn’t their problem. The Evening Standard editorialized that business owners had a vested interest in an oversupply of labor to keep wages low:

“The truth is, that this is a Government by no means interested in what are called working-men’s questions, but rather prejudiced against them. It is a Government representing the class of employers rather than the class of the employed — a Government of railway directors, of millowners, of merchants — a Government of which the chief intellect is Mr. Lowe, the virulent impugner of the working man’s capacity and honesty, and of which the loudest tongue is Mr. Bright’s, who is for the dealers against their customers — for the adulterators and users of short weight against their victims….They would rather not have any emigration if the truth were known. They would rather that the plethora of labour should continue so that wages may be low and the mills active.”

Some of the language used to describe unemployed workers seems really demeaning to my ears. From a meeting of the City of London Tradesmen’s Club, one attendee attributed “… the increase of pauperism chiefly to the monetary crash of 1866, and thought the best remedy was emigration. He doubted if education would decrease pauperism; the country was overstocked…” From the same meeting someone suggested that there should be forced savings from paychecks to cover setbacks or else the ratepayers (who paid for poor relief via the workhouse system) would become paupers. Another opined that it pauperism lead to becoming a criminal so paupers should be employed!

One Vicar at a meeting of an East End emigration group talked of working poor in his parish who couldn’t live on the pittance they received for their labour. His motion: “That though the depression of trade, and other causes, a large number of persons are unable to earn enough to live upon; that there is no prospect of improvement, and that emigration affords one of the best means of relief” Others wanted “…the waste lands of England should be cultivated first.” A report of some debate on the subject in Parliament seemed pointless as members were saying emigration wasn’t possible because they couldn’t know which colonies needed workers!

A happy event, but unfortunate timing for William Thomas Procktor and Elizabeth Brown that they were married (in a double wedding with Elizabeth’s sister Maria) on 11 March 1866 in St. John the Baptist parish church in Hoxton (Church of England, and no Quaker service that I’m aware of). Shortly thereafter – at the end of May – the financial panic started with the collapse of a London bank (Overend, Gurney and Company) and unemployment rose. By the end of 1869, a Staffordshire paper claimed there were 1.5 million unemployed in the UK. A number of charities, particularly in the East End of London, started promoting and funding emigration schemes as a way to provide work for those who couldn’t find it.

William and Elizabeth’s first child, William Alfred, was born in December 1866 and a second son in May 1869. By 11 June 1870, they were on the SS Medway, heading to Quebec (where they arrived 30 June) and then on to Ontario. We’re between censuses at this point so other than knowing that William had moved out of his parents’ home at 58 London Wall to 38 Gloucester Street, there’s no detail on their circumstances between 1866 and 1870.

A passenger list shows it was Kelshall’s Emigration Charity that assisted William and his family which suggests that they were in need of support. I haven’t been able to find anything detailing the exact arrangements the workers agreed to beyond the list which says that £1 5s was provided for them when they arrived in Quebec, equivalent to $6.25 at the time. One newspaper article said the cost of passage was £6 (about £700 in 2019 terms) and the emigrant had to provide half of that, via a weekly deposit made to the organizing charity. Some groups sought public contributions to assist in this work, viewed as a form of poor relief and also a way to improve employment prospects for those who remained on England.

It must have been a truly tumultuous few years for the Procktor family. By the 1871 Canadian Census, William, Elizabeth & family are in Hamilton, Ontario (listed as Weslyan Methodists, not Quakers). William’s occupation is Cabinetmaker which suggests he was able to find work.

The British Newspaper Archive has a number of articles from the late 1860s and early 1870s covering which types of workers are needed – agricultural laborers are in great demand, but they also list other skilled trades both needed and not needed:

“There is a steadily increasing demand for carpenters, buggy and carriage builders, wheelwrights, agricultural implement makers, blacksmiths accustomed to country work and shoeing, bakers, butchers, bricklayers, and brickmakers, with their labourers, masons, stonecutters, cabinet-makers, coopers, tanners, and curriers, market-gardeners, millers, painters and glaziers, plasterers, plumbers, tailors, shoemakers, tin and whitesmiths…Female domestic servants from fifteen years of age, in almost unlimited numbers, are certain to find immediate employment…Clerks, shopmen, or persons having no particular trade or calling, and unaccustomed to manual labour, are not advised to emigrate. Iron ship-building is not carried on in any part of the dominion of Canada, and it would be impossible to find work for men in that branch of business; nor can rollers, puddlers, boiler-makers, or those engaged in the kindred branches of trade, find profitable employment at the present time.”

There were articles in British newspapers about many ships with the unemployed leaving during the season (i.e. Spring and Summer) from 1868 through 1872. By 1875 it appeared the migration had slowed (or at least the newspapers had stopped writing about it). Possibly the employment situation in the UK had improved?

In November 1873 a third son, Arthur John, was born, and some time between then and 1877, when a fourth son, Herbert, was born in Peckham, London, they returned to England. I’m told passenger lists from this period were destroyed by fire and I have not been able to locate any records of the family’s return to London.

The Procktors show up in the UK censuses from 1881 on with the exception of Arthur John who I think returned to Canada in September 1893 on the Lake Winnipeg (Liverpool to Quebec), but I have not been able to find further Canadian records that are definitely his. He no longer shows up in the UK census records and I haven’t found a record of his death.

There is one more Canadian connection for the Procktors – Olive Marie, one of William Thomas’ granddaughters. This comes much later, in 1946, when she marries a Canadian soldier in Wales and then moves to British Columbia and settles there.

It would be nice to know a bit more about William Thomas’s time in Ontario and why he didn’t stay, but I have no family stories about this part of his life – beyond that he was a Quaker pioneer, which he clearly was not!