Looking into my 2nd great grandfather’s time in Canada in the 1870s, I filled in a few blanks on my family tree on Ancestry. A couple of the names rang a bell as ones my mother had mentioned, but I didn’t know how these people were related to her. I don’t recall ever meeting them, but in researching the family connection, it’s not surprising that my mother knew of them. It’s not clear how well she knew them, but it turned out she and they were second cousins – all three were great grandchildren of William Thomas Procktor who sailed to Canada in search of work in 1870.

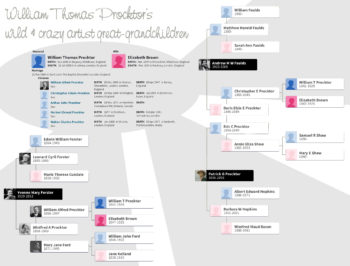

In the family diagram I have left out a few people to focus on how the three second cousins are related (for example, William Thomas had a daughter who died as an infant and another who never married who aren’t shown). Andrew Faulds was the oldest, born in 1923; my mother, Yvonne Forster, was born in 1929 and Patrick Procktor in 1936. All three were what people call “colorful characters” and also gifted artists. Andrew was an actor and an outspoken (and apparently sharp tongued) Member of Parliament. My mother was an actress and painter who struggled with mental health issues and then disability for most of her life. Patrick Procktor was a flamboyant painter and theatrical designer who found great fame very young and then struggled with being eclipsed by his friend David Hockney and alcoholism.

The British Newspaper Archive provided a number of stories about both Andrew Faulds and Patrick Procktor as well as my mother’s early acting career, so it’s possible some of the information isn’t the whole story – newspapers typically stick to the more sensational parts of any tale.

Embed from Getty Images

Andrew Faulds was born in 1923 in Tanganika (now Tanzania) – his mother Doris Procktor had married a Presbyterian missionary, so his early years were spent in Africa until his return in 1929 (from Durban, South Africa). He went to school in Edinburgh and then to Glasgow University, and was said to have a “rich Scottish voice” – also described as “booming” and “unmistakably loud and thespian” – even though he was only loosely Scottish (his father was born in Lincolnshire, although his grandfather was from Ayrshire).

The young actor worked in movies (Cleopatra, Jason & the Argonauts) TV and radio (Jet Morgan in Journey into Space – 1953-58) and later did a stint on Equity’s council. He was persuaded by Paul Robeson to join the Labour Party in 1959 as a way to act on his views on social and racial injustice. He protested the Vietnam War, wanted full labeling of bread ingredients, no VAT on theatre tickets and condemned Enoch Powell as “unChristian… unprincipled, undemocratic and racialist“

Andrew was tall, striking and unafraid to stand his ground on matters of principle. He first ran for Parliament in Stratford-on-Avon but lost. In 1966, he ran as a Labour candidate for Smethwick and won. His Conservative opponent ran with a vile racist slogan: If you want a ni**er neighbour, vote Labour. Even for 1966, that’s breathtaking! He didn’t mince his words once in Parliament, calling the shadow Foreign Secretary a fat-arsed twit, and being reprimanded by the Speaker for calling the US President (Ronald Reagan) an incoherent cretin. From The Stage’s obituary in 2000, “The greatest compliment ever paid to him was that he was a man of unshakeable principle who never, anywhere, said a word in which he did not believe. “

He continued to do acting and voice over work as his schedule in Parliament allowed and said that his constituents liked seeing him on the telly! A fellow Labour MP described Andrew as wonderfully outrageous in an endearing way, although in the Guardian’s obituary they said he was a House of Commons character who never managed to live up to the role he envisaged for himself.

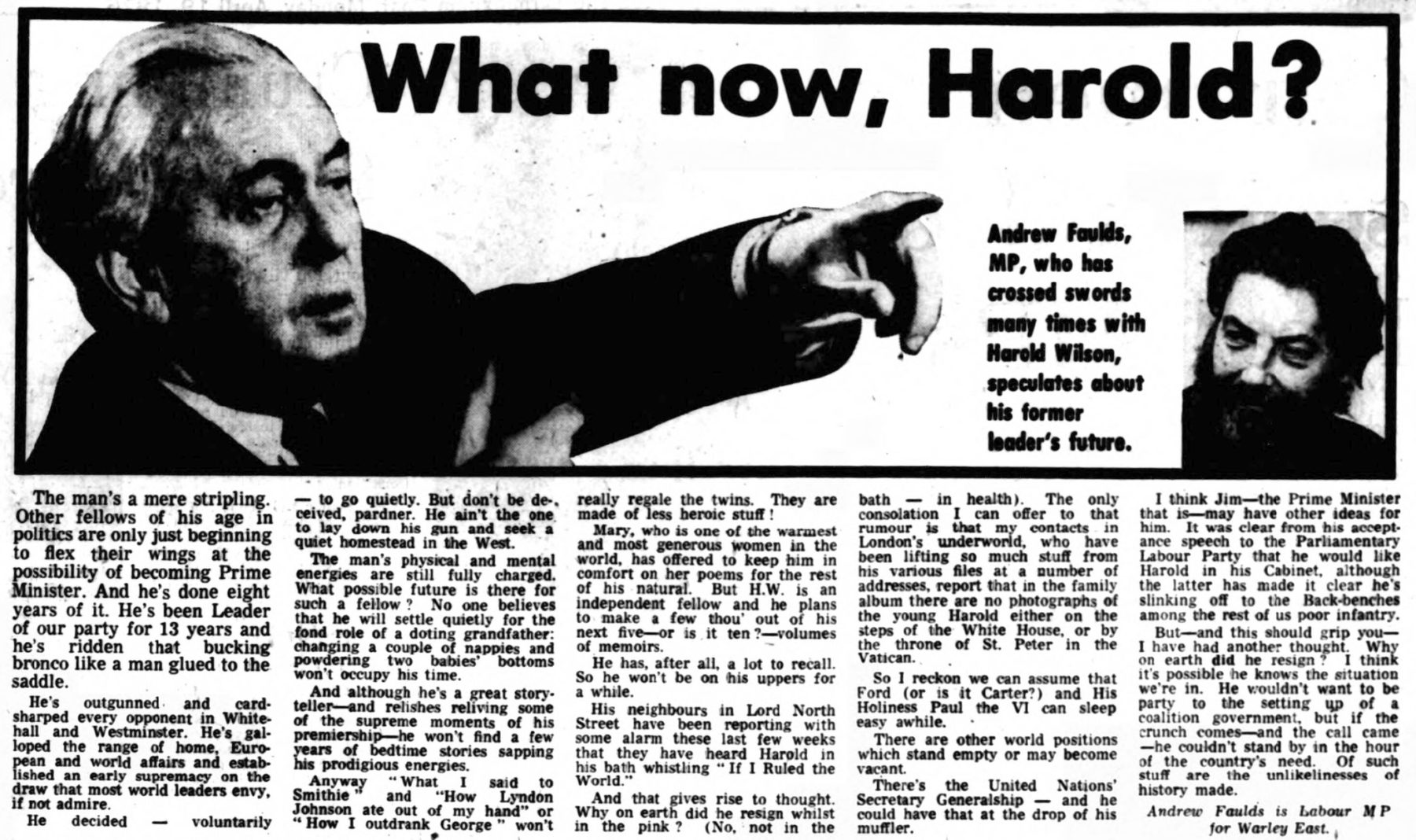

Perhaps his irreverent style is best shown in his own words – a guest column from the Birmingham Post in 1976

My mother, Yvonne Forster, was an only child whose escape from difficult family relationships was into books, drawing trees, and acting in school plays. Her mother wanted her to become a doctor, but Yvonne wanted to go to RADA (Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts) which she did in 1945, winning a prize in the RADA matinee for best performance in a character part in 1947. From 1948 through 1954 (when I was born) she worked in a variety of repertory companies around England and Scotland – interestingly written up in local newspapers without which I’d have no record of her work. The theatre critic at the Hastings & St. Leonard paper appeared to have a huge crush on her – I’m sure she was a good actress (my father said she was, and he was never one to offer praise just to be nice), but he just gushed. From 1952, in a review of The Seventh Veil:

…without an actress able to depict with convincing realism . . . the progress of the pianist Francesca from a gauche schoolgirl to graceful womanhood, the play would lose much of its intended effect. Here Hastings theatregoers are fortunate indeed, for Yvonne Forster fulfills this condition beautifully. This presentation is another triumph for this resourceful young player, who portrays Francesca with a combination of a sensitivity and strength that makes a deep impression.

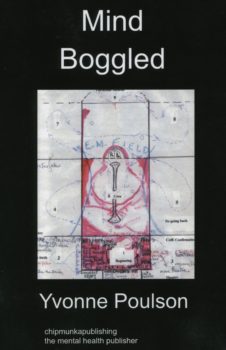

My mother’s struggles with mental health problems and being accepted as she was were life-long and muddled. In 2009 Mind Boggled was published, talking about how she saw things versus what she had been told she should see. “My own thinking has only now, at the age of 75, been sufficiently freed from the various cover ups and coping strategies I used to side step stigma, and the many different pathologies attributed to my condition along the way, to allow me to find my own mind again…I had tried to be all the contradictory things I was told I should be – with very little success.”

Yvonne painted – oils, water colors, pen & ink sketches and occasionally prints – most of her adult life. A few works were commissioned portraits she sold, some for gifts, but mostly it was just what she wanted to do,. She trained for a National Diploma of Design, went to Eastbourne Teacher Training college, worked as an art therapist with patients at Leybourne Grange in Kent and Roffey Park Hospital, Horsham. She toured with the Graeae Theatre Company later in life, sang with an Elizabethan madrigals group and worked with the South London & Maudsley mental health teams as a volunteer.

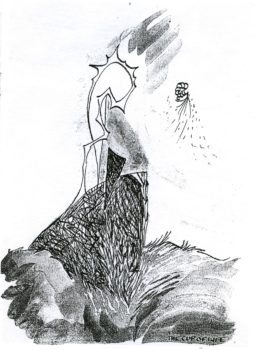

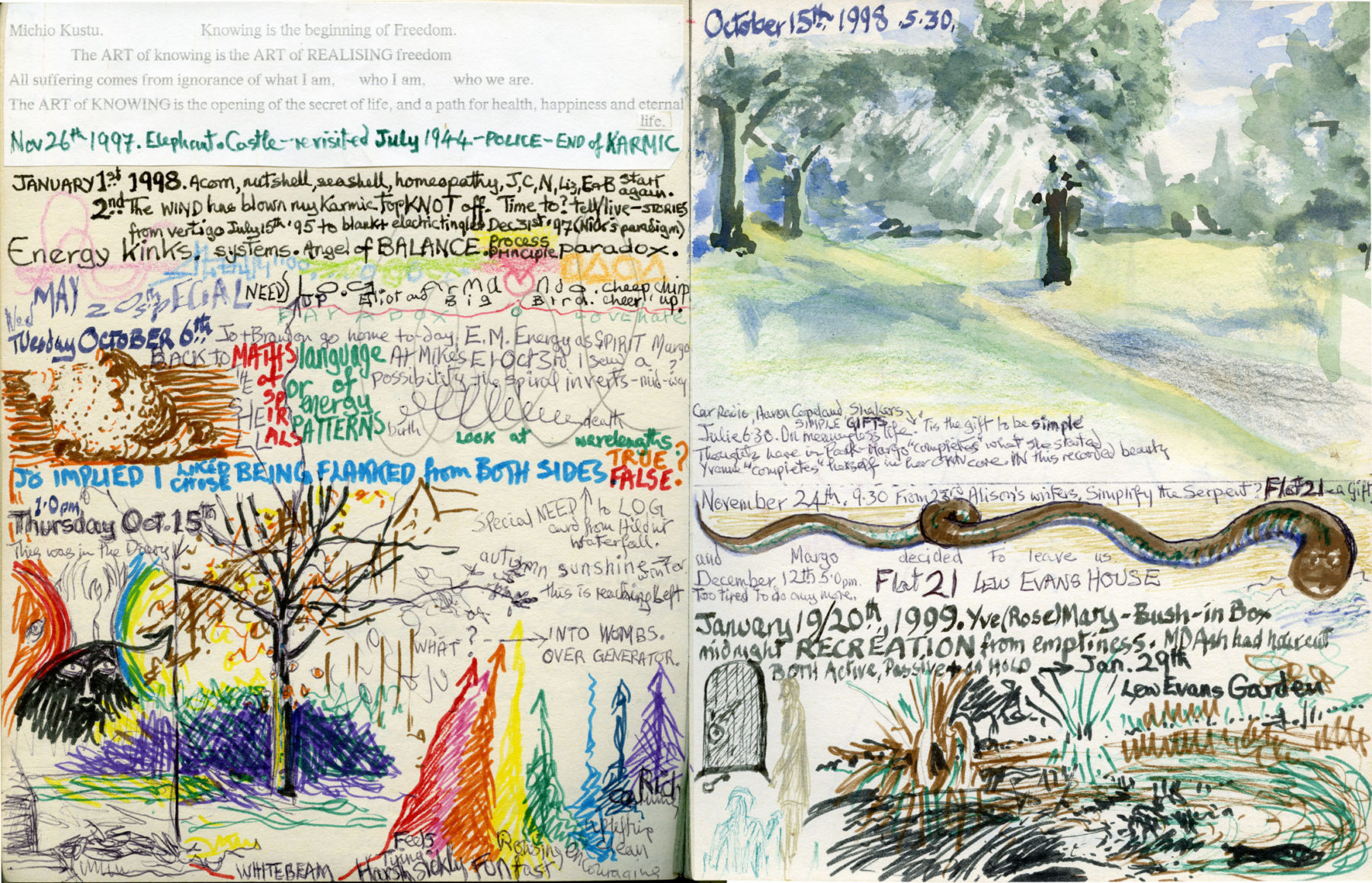

Her own words and pictures (this is one page from one of many journals she kept) perhaps best illustrate her mix of struggle and artistic expression.

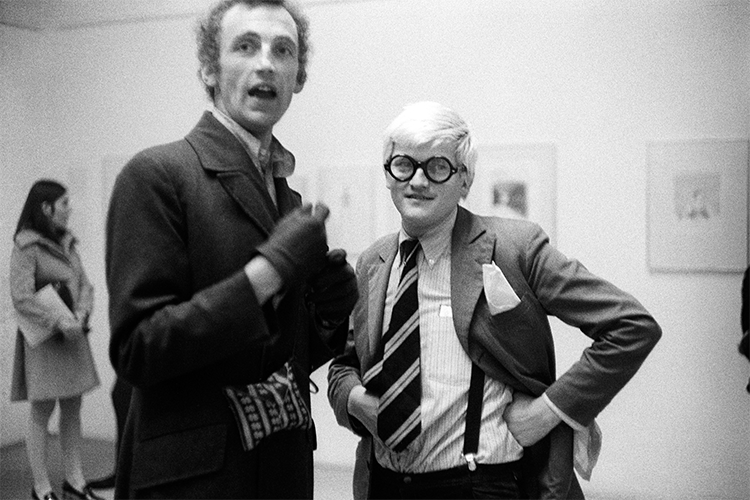

Patrick Procktor had a difficult start in life – his accountant father died when he was 4 and he had to leave his private school and skip Oxford when there was no more money. He went to work for a builder’s merchant, then did National Service with the Royal Navy in 1956 which led him to learn Russian. In 1958, older than the other students, he went to the Slade School of Art. A fellow student remembered him: “He was an extraordinary-looking chap – thin as a stick, and 20ft tall. He was very much an extrovert.” He wasn’t that tall, but at 6 ft 6in, stood out. His first show after graduation sold out and he and David Hockney were art superstars in London in the swinging sixties. Procktor drank too much, became great friends with Princess Margaret, traveled and fell in love with a young man who dominated his work for two years (which led to a failed one man show in New York in 1968 showing only portraits of his lover). In 1973 he surprised everyone by marrying a young widow, Kristen Benson, and had a son, Nicholas, with her. She died in 1984, and the combination of many factors – alcohol, professional decline (he wasn’t in fashion any more), envy of David Hockney’s success, and in 1999 a fire in his flat which destroyed many of his works, left him adrift and at one point in prison! His mother called the police as he’d threatened to kill her. He died in 2003.

An internet search will show lots of his work – here is one called Me or a Quiet Dinner

I’m perhaps not surprised that my grandparents (my grandmother was Winifred Adelaide Procktor) didn’t socialize with Andrew or Patrick – their very conventional middle class life wouldn’t have easily accommodated the Labour Party MP or an openly gay “modern” artist. It somehow – to me -seems a shame that the three second cousins didn’t have a relationship as they appear to have much in common and might have enjoyed the company.