On page two of the first notebook of his draft memoir, David Poulson relayed a wildly exaggerated tale about school he’d told his mother and noted “Truth and my imagination were already uneasy bedfellows“. One unambiguously true statement! David’s school days at St. Edwards, Oxford, ended in July 1942 after completing School Certificate and Higher School Certificate in French and Spanish (he took History as well, but described that in his memoir notes as “less successful”). Each branch of service had presented at St. Edwards, and David’s notes tell of two uninspiring recruiters (for the Army and Air Force) and one blond Navy flier who “scooped the pool“. He couldn’t enlist until 17, so he planned to join up on his birthday in February 1943 and, in the meantime (according to the memoir notes) “I was free to enjoy life to the full. I wanted the evening use of my father’s car. Cars equals girls. ” My educated guess is that the memoir is a blend of reality and a good story, but his notes are the primary source for David’s war years and first real (and only non-theatre) job with the British Overseas Airways Corporation.

To fund his hoped-for adventures, David scanned ads in the Bournemouth Echo and applied for a job as a milkman – driving essential. He didn’t drive, but got the job and asked Gamps to teach him. David’s memoir notes mention a provisional license – a driving test was introduced in 1935 but was suspended during World War II. Apparently being a milkman was harder than it looked – “My first day solo on the milk round was a complete disaster.” – but none of the mishaps involved his newly-acquired driving skills. He forgot the key to unlock the milk churns, rolling huge milk churns proved tricky (“…it fell sideways with a crash and the yard was transformed into a lake of milk”), and a lorry loaded with pipes smashed the milk cart’s windscreen, leaving David to face his foreman’s anger when he returned to the dairy. He didn’t get fired that day, or the morning he turned up late still in his dinner jacket from the night before, enraging his foreman again: “If you bloody well think I’m paying ‘ya bloody wage this week, you’ve got another effing think coming.” Image used under a CC license courtesy of Alwyn Ladell.

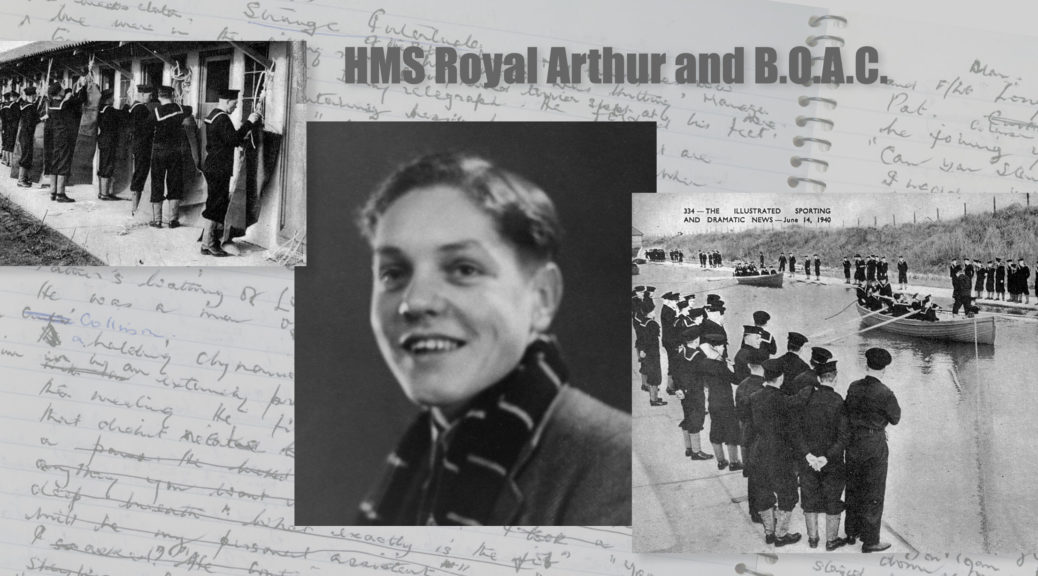

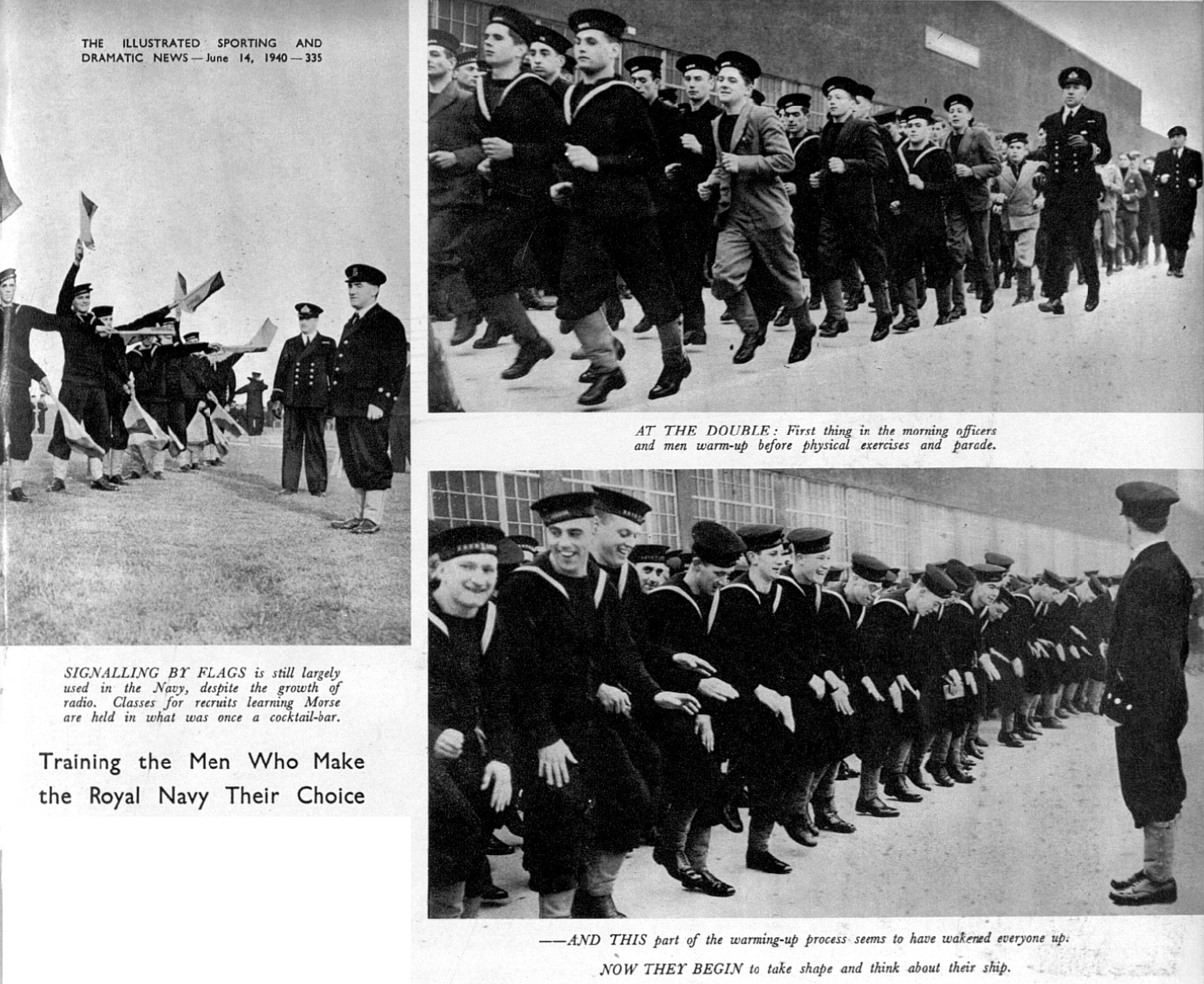

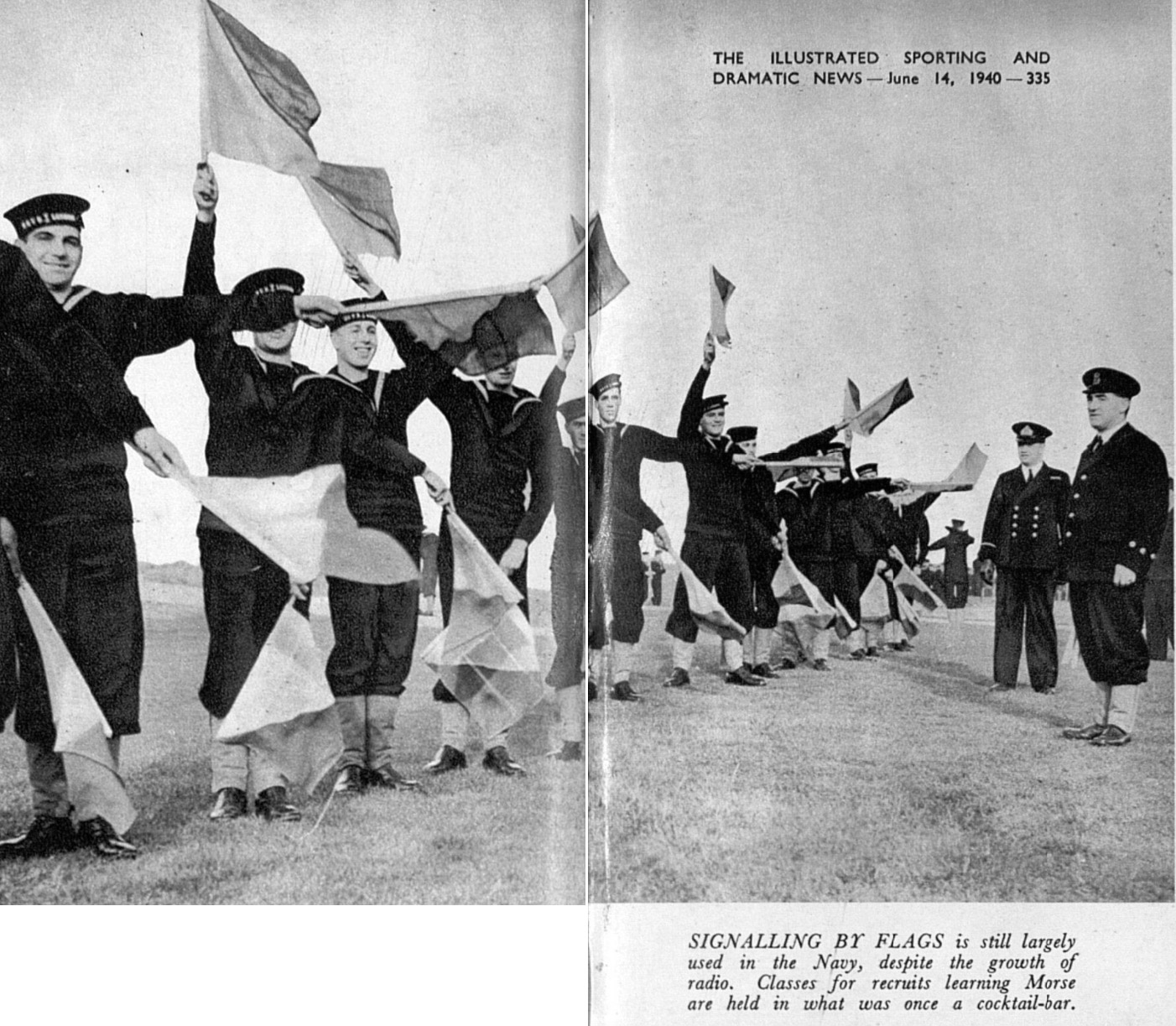

David apparently viewed his work experience, plus a very public defeat in a tennis match (he’d over-sold his tennis skills and been outmatched by an RAF champion) as “…preparation for the rigours and injustices of service life which started at H.M.S. Royal Arthur, Skegness. I arrived with a trainful of other recruits at what had been a Butlins Holiday Camp, swept by a February wind which had come straight from Russia.” He wasn’t impressed by the 3-bed room he was assigned and claims he found a different chalet with much nicer beds and softer mattresses which then became home for the three of them. He also didn’t like “…the hours the Navy kept. ‘I don’t reckon this getting up at six, having a rotten breakfast and then waiting til morning divisions at 8:30.'”

David suggested (and talked his cabin mates into) buying buns and lemonade from the NAAFI, getting up two hours later, at 8am, eating their purchased breakfast and then joining others for the day. They of course got caught and disciplined – confined to camp for three days. “No great loss. Wartime Skegness had little to offer.” He continued for an unknown amount of time until headaches led him to an eye doctor. David was given eye exercises to do but couldn’t stay in the Navy. He returned to his parents in Sandbanks – his mother was overjoyed but Gamps asked “What are you going to do, old boy?” David had no clue but Gamps offered “I’ll arrange a meeting with a man called Collins He is something quite high up in aviation.” That meant a trip to London to meet Mr. Collins. Mr Collins worked for the British Overseas Airways Corporation.

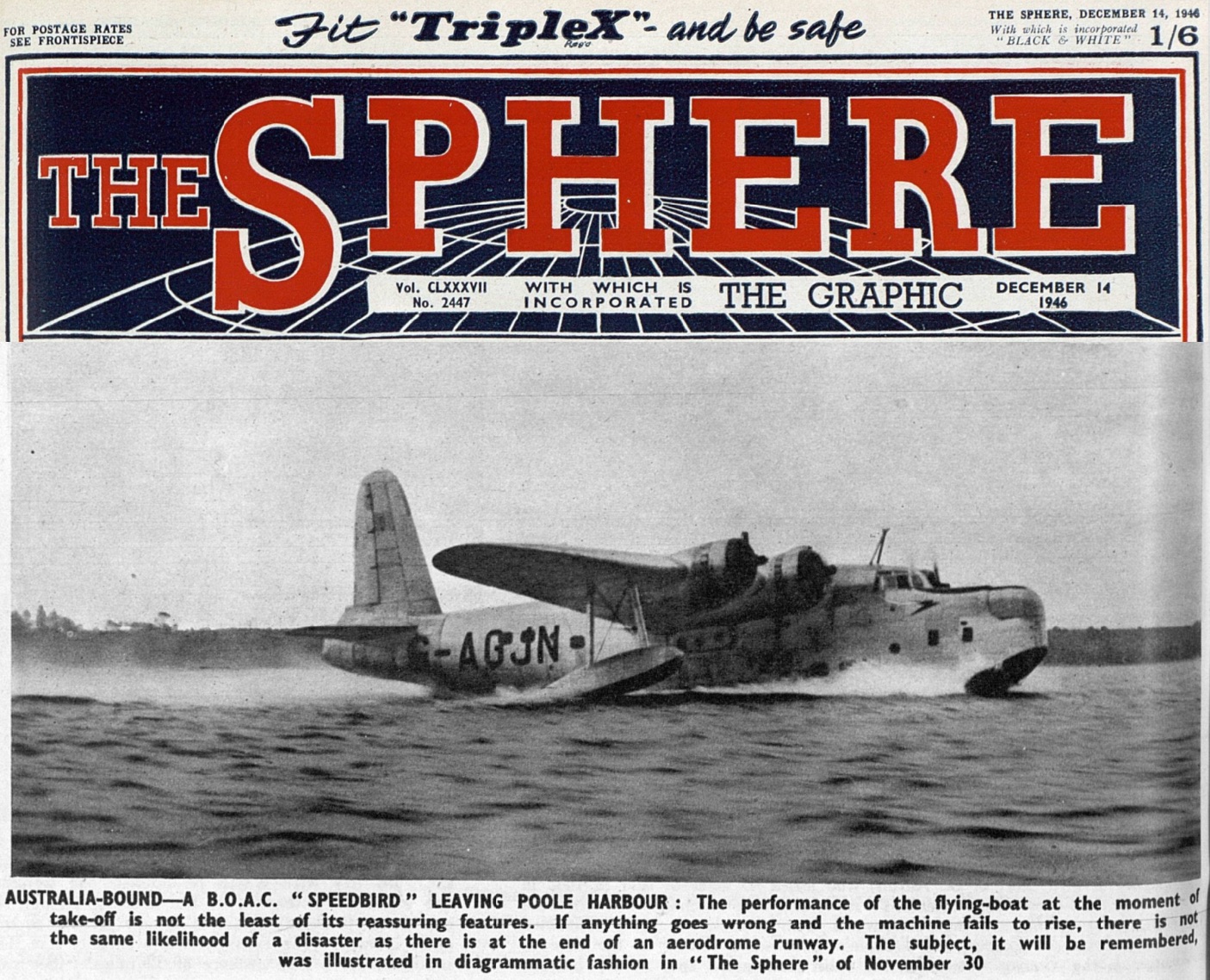

During the war, BOAC provided transport services for the RAF and their African and Middle Eastern routes centered on Cairo – BOAC was not the military, but not a private company either, overseen by the Secretary of State for Air. They also carried airmail, freight or passengers as needed – all operations were through National Air Communications at the Air Ministry. Poole (near where the Poulsons lived at the time) was the base for BOAC’s flying boats. Mr. Collins asked if David spoke any languages – French & Spanish. He was told he’d be working with a team of four on getting the airports ready for Middle East routes – Malta, Sicily, Cairo, Khartoum, North Africa. He was introduced to the others on the team, asked if he could start next week, and left without knowing what he’d be paid.

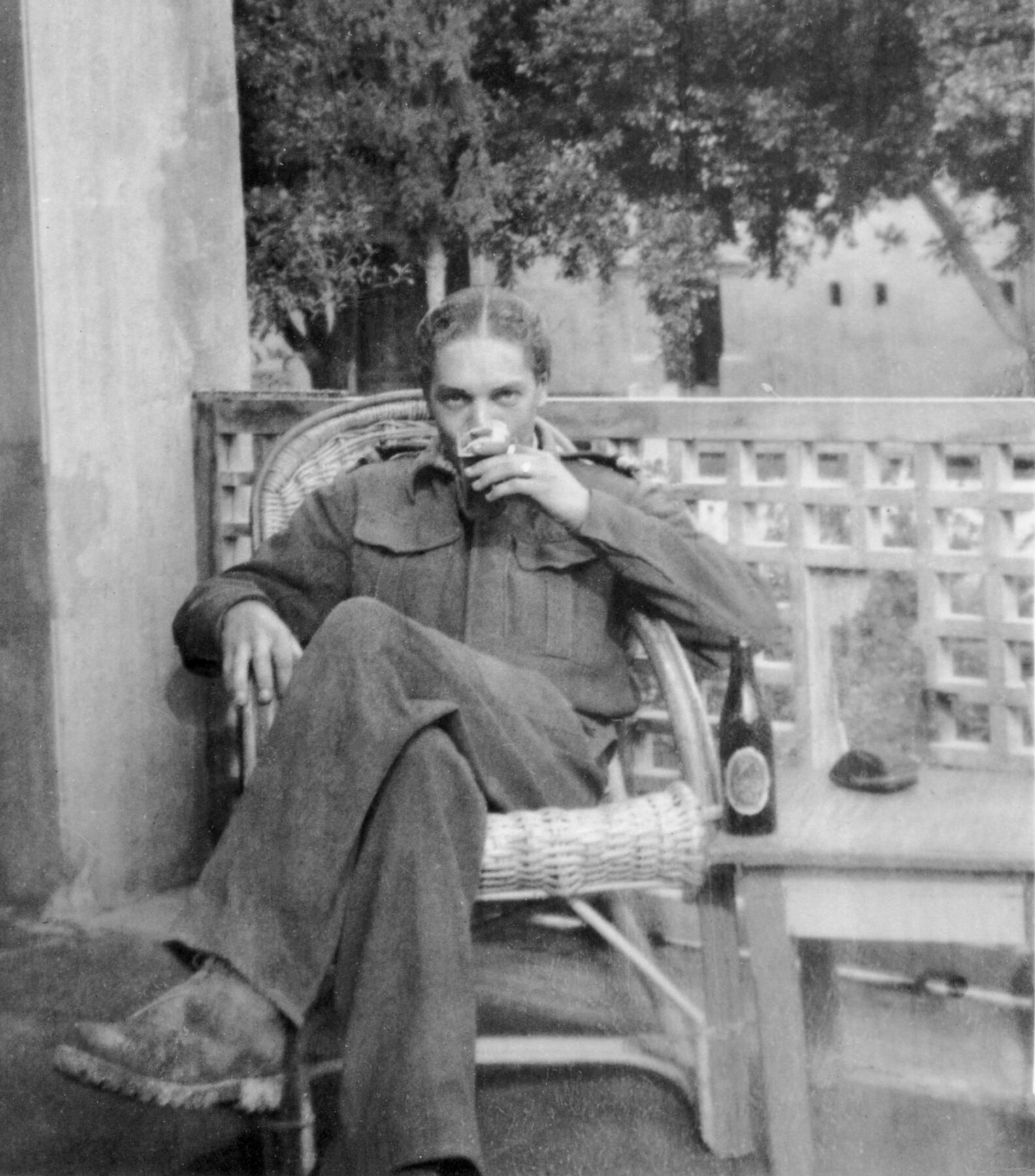

I’m not sure if there was any awkwardness about serving during World War II in a logistics role versus in the Royal Navy – the way the stories were told when I was young, I was left with the impression he was in the Navy during the war, but the memoir notes are unambiguous. And this photo is too – a very young David in his BOAC uniform. There are no details of any training or other preparations and the next part of the story picks up on a freezing January afternoon (I assume 1944, but the memoir notes don’t say) when David flies to Portugal and stays in a hotel for the first time. Apparently their report on the airport was written in four hours and they had “…three wonderful days, swimming at Estoril and exploring nearby villages like the small fishing port of Cascais, completely undeveloped in those days. We went shopping in Lisbon filled with things non-existent in wartime Britain. At night, the city was ablaze with lights and throngs of people filled the streets.” I’m sure it was a welcome break from the wartime routine, but it’s so like him to make the whole experience sound like a luxury holiday.

Mr. Collins gave them two days off to take presents home to family (David took bananas, unseen since the beginning of the war) before they left for Biscarrosse and Marignane in France to choose a base for the Sunderland Flying Boats and Dakotas for the Middle East routes. Atlantic gales versus Mistral winds. The memoir notes take a long detour in Marignane as he fell in love with a French woman from Orange, Marie-Antoinette Odinet. After he left for El Adem (near Tobruk in Libya) , she wrote to say she was pregnant. Marie’s Catholic family apparently refused to permit a marriage but she asked for financial help. The memoirs have a preposterous sub-plot about Indian gold left behind with David for safe keeping (in Marignane) by a Polish pilot who was later arrested for smuggling. David says he bought a house by the sea in Carry-le-Rouet with the gold and when Marie needed money, he stopped off on his next trip home, sold the house and used that to send money to Marie every month until she married and her husband wrote to tell him to stop. I have no idea what to make of that, but as far as I know, David and Yvette never met and that charming photo is our only connection to a French older sister.

While airports were being built, there was often an RAF mess BOAC staff could use. I’m not sure if there was business that took David to the officer’s club in Derna (on the Libyan coast, west of El Adem), but this photo was taken there – see the note below about nurses in Derna. RAF El Adem, where he was based, was run by German and Italian POWs. “No one seemed to find this in any way odd. But this was an odd airfield run by a very odd man.” There were some snobbish comments about the commandant having risen through the ranks. David apparently upset the Wing Commander running El Adem when he crawled back to his hut after a drunken birthday celebration in the mess destroying the perfectly straight lines of a flower bed that a German POW gardener had to maintain (daily inspections by the Wing Commander). “Civilian suede desert boots left unique footprints in the sand before I fell to my knees for the last part of the journey.” As a civilian, there wasn’t much the RAF could do other than send him home, but David apologized and “our relationship was frosty for the rest of our stay”. I assume the boots in the above picture are the ones he wore throughout his assignments in North Africa.

Apparently the officer’s mess in Tobruk was much more to David’s liking and there was a great beach as well. It was about 30 minutes drive away with limited options for transport, but a postcard with a for sale notice resulted in David buying a bike:

“For Sale, B.M.W. opposed twin cylinder 750cc ex Kraut bike. Altered differential. No side car. No Machine Gun. £25”

David gave it a trial run and bought it from a departing South African pilot. “It was my passport to freedom from the all male presence of the Wing Commander’s prison camp. Rumour hat it there were female nurses in a hospital in Derna.” David arranged with a mechanic on base to alter the differential back, add a side car and he set off on the 120-mile trip. A yellow sticky with notes suggests he looked back once too often and hit a telephone pole, sheered off the side car and ended up buried under a mound of sand. There’s something about getting an ambulance to Derna. Not sure if the above photo was from that trip or another one!

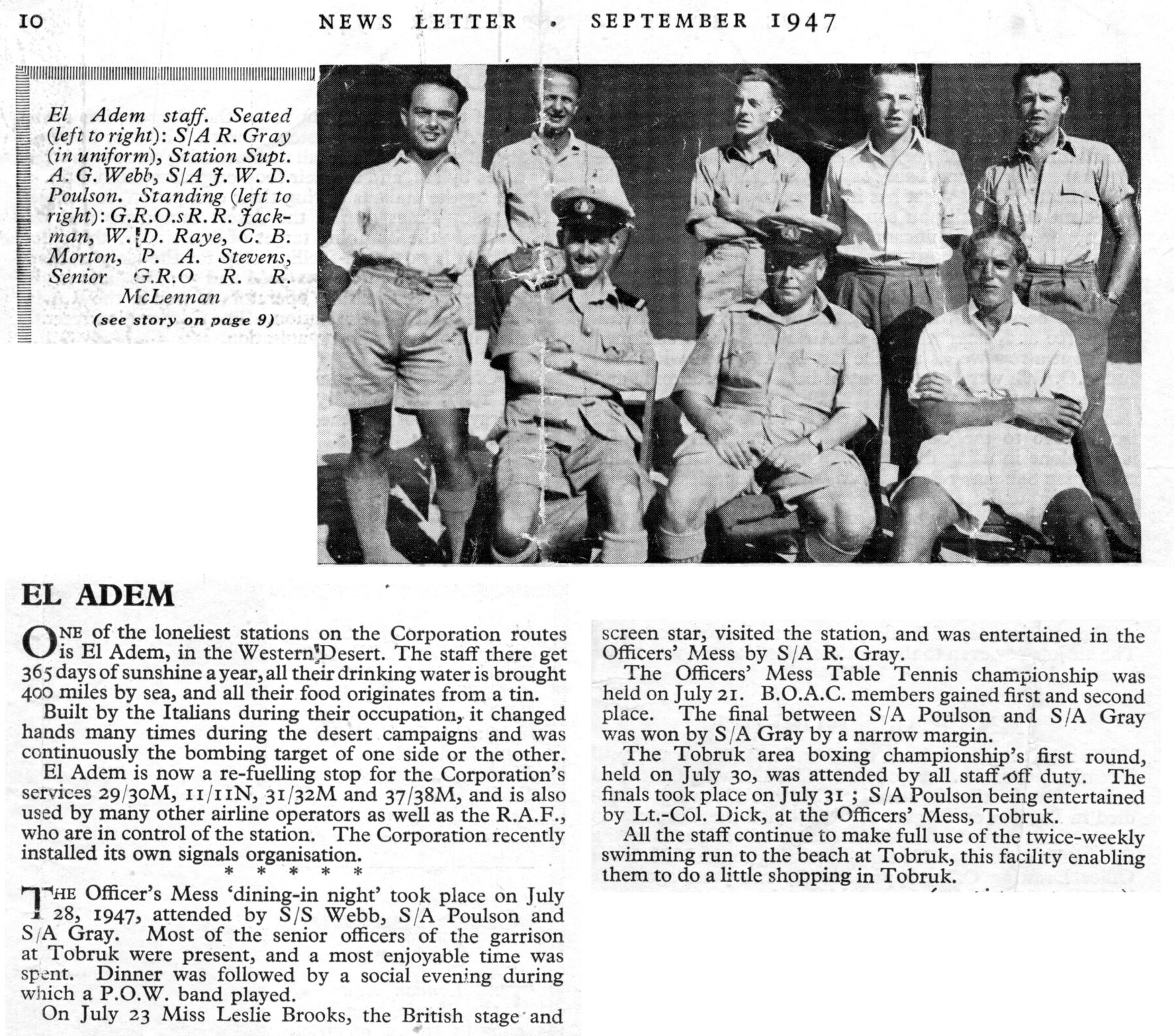

BOAC had an employee newsletter, and the September 1947 edition featured a photo of the El Adem staff, including a very tanned Station Assistant Poulson. There was a story in the memoir about a Christmas treat before going home for 10 days leave – a fancy-dress officers vs. other ranks football match. David borrowed a nightgown from a nurse in Tobruk and a donkey from a local family and got pretty bloodied by the other players pulling him off the donkey. He took the bloodied nightie home for Christmas where it was discovered by his mother when she unpacked his suitcase. They ran upstairs after there was a loud shriek, “…where my mother was holding the bloodstained nightdress. ‘I don’t mind what you do in these dreadful countries, but do you have to bring the trophies home?'” He thought he had a team photo with him (but of course didn’t), but Gamps figured, given all the blood everywhere: ” ‘Honestly, Billie, unless he insanely murdered the girl, I think his explanation is more likely.’ “ The fact that this story is in the memoir shows me how much Dad like the lovable rogue image of himself. After Christmas it was off to Cairo as the team’s work in El Adem was complete – possibly this was December 1947?

January 1, David took the Sunderland flying boat from Poole harbour, saying good bye to his parents: “My parents, who saw me off, were very impressed. I had introduced them to the team who for once were on their best behavior.” The trip had stops in Marignane, L’Etang de Berre; Augusta, Sicily; and “…landed on the River Nile by moonlight. Cairo by night looked magical and the air as the launch took us was warm and musky.” He wasn’t as impressed with the city in daylight the following morning – “…dusty, shop-soiled, and generally rather dirty, but bustling, noisy and overcrowded.”

The memoirs quickly turn to a tale of taking a girl out in a borrowed motor cycle and ending up by a waterworks, getting arrested as a suspected Jewish spy. He writes that he and Penny (apparently the daughter of the British Consul) were held for 2 days and nights, and that after some derring-do on David’s part, he managed to knock over a guard and make a phone call to Penny’s father to explain what had happened. There had been some talk of taking them to a notorious prison camp in Banha, mention of which apparently got the Consul’s attention. Not long after they were taken from their cell to an office and saw “…cars led by a be-flagged Rolls Royce drive into the compound with two motor cycle outriders. With a gesture and a rather forced smile we were ushered out.” The memoir claims villagers cheered as they thought King Farouk had come to visit! No more stories about Cairo, but some photos of tennis (not sure where the BOAC cafeteria was)

The final stop was Khartoum, Sudan, where his billet assignment – with Duncan, a bank clerk who also acted – turned out to have a huge impact on the rest of his life. Duncan invited David to some of the performances and auditions for the next production. David read, got the part, and although it was small and he was not sure what he was doing, afterwards was given a business card by a man who told him “When you get home, give me a ring and I might be able to help you. You’ve got a very good voice.”. The man was a BBC radio producer.

“I didn’t go home to my parents and tell them I’d left this reasonably secure job for no better reason than that I wanted to be an actor. I knew what my father’s reaction would be. Rather, I thought to get a job first and then let him know.”