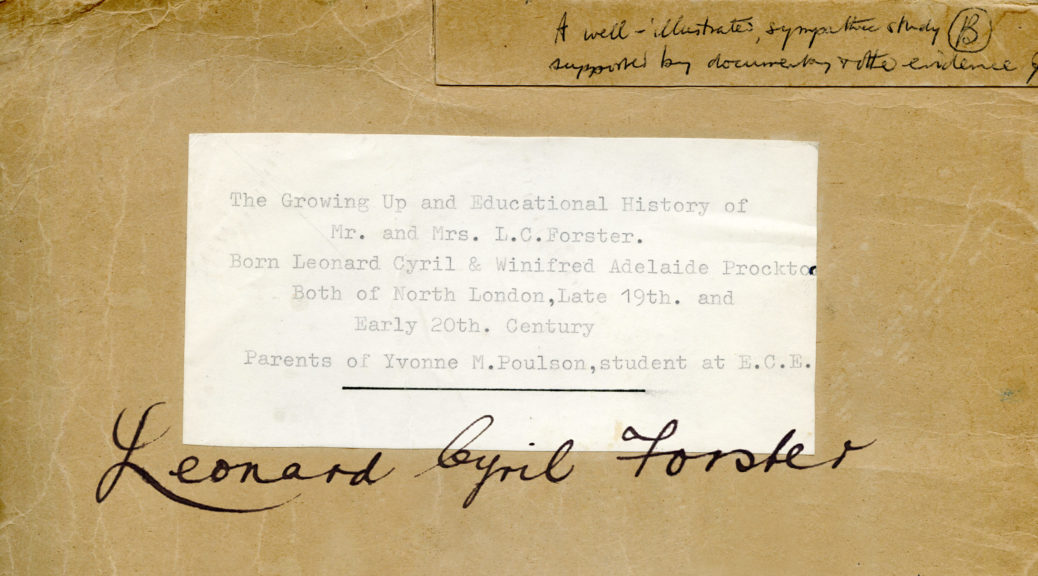

I provided an overview of my mother’s social history of her parents for teacher training college in a separate post. This is the detail section for her father, Leonard Cyril Forster. I scanned and converted into text (production note: OCR software is still sadly an almost-success where fixing up errors almost negates the time saved) to improve readability, but the spellings (English versus US) and rather odd sentence structure – more like notes than an essay – I left intact. You’re seeing what my mother turned in – it surprised me to see such ragged work, but possibly she was pushed for time given other coursework.

This family tree has been constructed by me (in 2018, on Ancestry) using a variety of public records (census, birth, marriage & death, etc.)

Narrative of Leonard Cyril Forster’s life and family-my father.

Len, as my father has always been called, was born in 1895 to Edwin and Marie-Thérèse Forster when his mother was 37 years old.

He was the third of four sons, much to his mother’s sorrow as she herself had only sisters and would dearly have loved the promise of feminine company. Len was a pretty baby and she dressed him as nearly like a girl as she dare while he was tiny. There was a gap of 6 years between himself and his elder brother and over 4 years between himself and his younger brother so he saw very little of them, cannot remember playing with them; as he was the only one of the four to win a scholarship from Stoke Newington High Street Board School to ‘Grocers’, a London Guild School he had very little to do with them, nothing in common with them and scant feelings for them.

His father was a hard working and successful surgical instruments maker with no cultural interests and a ruthlessly authoritarian way of ruling the home with his cane. The oldest boy was destined to follow father into the business so was not given the chance of a scholarship though he was the brightest. Horace did not last 2 years before he had fallen out with father, been shown the door, and struggled away on his own to an excellent job in aircraft engineering. However Horace’s son still carried the chip on his shoulder of his father’s lack of educational opportunity until his death last year. The Boer War meant a great deal of work for medical suppliers and Mrs. Forster went to help her husband more and more regularly, leaving the baby in the care of various maids, one of whom resorted to playing ‘ghost’ to keep the baby quiet.

That performance was never forgotten; 4½ is a very impressionable age. Marie-Thérèse’s own father, Mr. Cundalé had been a ‘city gentleman’ an interpreter at Palmerston House, Bishopsgate and such a situation had never arisen. The most she had done was a little dressmaking to help the family. It is not known whether her mother was French, or English.

Len’ s early memories, apart from the ghostly maid in the sheet, were of playing with sand and water at the local school, (Wilton Road Board School, Dalston) of the thrill of hearing Margate municipal Orchestra playing in the Cliftonville band stand at the age of 7, specially the violins; this thrill and love became deeper as an early born sense of solitude and defensive attitude closed up all but a little social experience. As his parents were not enthusiasts for higher education he went into the commercial sixth form at Grocers losing his chance, of taking Senior Oxford. He started shorthand; then he had appendicitis. The abcess burst and caused acute peritonitis with a long convalescence during which he polished up the shorthand to quite a high standard; then back to school for a short time after which two more operations. By now the hope of achieving anything at school was fading, the parents urged him to find employment and he took the first thing offered in an exporting firm where a boy from school was already working He became a glorified errand boy. Len was shaken by the dreariness of the job, polished his shorthand, saved for a secondhand typewriter and learnt to type from a keyboard diagram. He applied for a job with another export firm as a clerk and got it.

He became interested in insurance and started reading about it, then noticed an advertisement for a shipping clerk in a shipping agents and insurance brokers (members of Lloyds of London). A shorthand and typing test got him the job and there he stayed until the 1914-18 war.

His love of music had been fostered by a thriving musical life at the Grocers school where the religious worship and music were interdependent, though he had not had the chance to learn an instrument, only to sing. In 1912, now settled in a job, he bought his first violin and went seriously about teaching himself to play it.

Within a year he was able to join the Bishopsgate Institute Orchestra and later to play with others at the Pleasant Sunday Afternoon group, soon to become The Brotherhood movement, of the Non-conformist church. Also the Rev. Morgan Gibbon of Stamford Hill congregational church had been exerting an influence more based on response to oratory and beautiful language than theology, since the boy was 12 years old until this time. It was at the Abney Brotherhood group that Len met Wynne-Winifred Adelaide Procktor, also of Stoke Newington, who sang very well and played the piano; they started playing violin and piano sonatas.

Then came the 1914-18 war. Len’s operations had left him in a state that resulted in a 6 medical grading and he was rejected by all the services. There followed a series of ‘white feather’ incidents casting aspersions on his integrity with which he became most exasperated, and in frustration and desperation joined the Red Cross at Netley as an orderly. The work was deadly and on his first leave he went to the H.Q. to ask if there were not some job they could offer which made better use of his previous experience, preferably something in France. They offered him a post on staff H.Q. at Le Havre which he joyfully accepted, and with atrocious French learned at school but with sound grammar, a good ear, and the necessity to speak french in a billet where no-one spoke english, his education in the french language was completed. Also the daughters of the house both learned the violin and helped him with his playing and their professor found him a lovely violin at a reasonable price which he is still playing to-day.

When the war ended jobs were not easy to find, but he still would not return to his old firm who were happy to have him back. This taste of a different life had re-awakened a recurrent desire for power to break away from the rut. Through friends he was offered a post with McAndrews shipping line in their Barcelona Office, but he was required to speak Spanish. So for a month he hectically swotted at Spanish from books and by the same token of living with a Spanish family who spoke no erglish, after a few uncomfortable weeks he became competent to conduct business in the language. The firm took on the agency of The British and Foreign Marine Insurance, and having worked originally for LLoyds brokers, he was asked to establish the business. Contacts thus made led to his applying for a job with the British and Foreign for whom he worked until his retirement.

He joined Lloyd’s orchestra and later the Insurance orchestra which played for all the big operatic and dramatic societies in London.

He married Miss Procktor in 1922; she gave birth to a daughter in 1929; and in 1933 he became recurrently ill with a complaint which was not diagnosed for 5 years as being yet another result of his appendicitis in 1910. After a correct diagnosis a cure was effected.

For periods of his life he was an avid reader and this also extended his education and helped to compensate for his irregular social life.